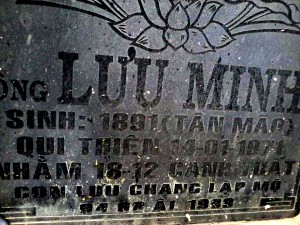

Grandfather’s new gravestone shows his date of death as 14 January 1971, a year earlier than my husband remembered.

I thought a date carved in granite would be right, but my husband said the date of his grandfather’s death on the gravestone was wrong. “I remember it was a hot day in 1972,” Luong said even though the grave lists Grandfather’s death as 14 January 1971. “You can’t be sure,” he said. “It could have been changed for luck when he was reburied. Or because someone wanted to make a claim to having inherited land at a certain time.”

Grandfather Lưu had a dramatic death that would stick in anyone’s mind, but Luong would only have been eight or nine when it happened. I asked my mother-in-law when Grandfather Lưu died. She said to use the grave. She didn’t know any reason it would be wrong. Má wondered why it mattered so much if someone died in 1971 or 1972. It was so long ago, and the years are so close.

I drive my husband and his family crazy in my quest for accuracy. Maybe it’s the years I spent in science. When looking back on all the memories in a life, a year doesn’t seem that important. But once you put an event down on paper in a line-up of time, it stands out and defines the events around it. Often a new realization comes of why things happened the way they did. I needed a date for the book, so I took it from the gravestone. It’s hard to trust a childhood memory over what’s written in stone.

Then, while I was going through old albums searching for pictures from Vietnam, I found a photograph of Grandfather Lưu’s original grave. The date of death read 2 February 1972. “I knew it,” my husband said. But why would the date on the new grave be a whole year off?

The error must have happened when the cemetery Grandfather was buried in was slated for bulldozing. Grandfather’s bones were placed in an urn in a temple and labeled by monks using the moon calendar. Because Grandfather died right before the Lunar New Year, the year of his death would still be 1971 in the moon calendar. If the monks subtracted another year by mistake and wrote 1970, later, when the family came to rebury the remains and converted the date back to the Gregorian calendar, the day of death would be 14 January 1971—the date on the new gravestone.

This must have been the case since the new gravestone gives the date of death a year earlier in the moon calendar as well. The year given is Canh Tuất, the year of the dog (ending 26 January 1971) instead of Tân Hợi, the year of the pig (ending 14 February 1972). Interestingly, the date of birth is also different between the two markers by seven years. We don’t have an explanation for that.

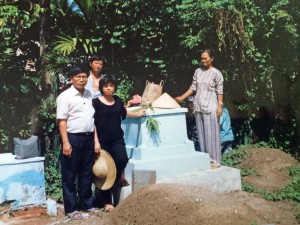

Family members getting ready to move Grandfather’s grave. Around them graves have already been removed.

Conversions are ripe for errors—I double checked all my numbers just writing this down. I wonder how many dates on the other graves I’ve used as cross-references are wrong. Since Luong’s other grandparents weren’t born on the cusp of the Lunar New Year, the same error isn’t likely on their graves. One thing I’ve learned is that sometimes memory is less fragile than what’s written in stone.

tjqerz

0txvjt

b9sj4h

Hello, everything is going well here and ofcourse every one is sharing data, that’s actually good

At least two of my relatives have their solar birth days converted as if they were lunar dates. That was done by the authorities in the early 50s and they could not correct them. Lunar conversion itself can be very complex. When I was compiling a list of family members spanning five generations, I came across several lunar dates off by one day which might reflect timezone difference depending on which system is used. Reluctant to question those of higher generations, I quietly added to my program a way to override calculated lunar dates.

“I drive my husband and his family crazy in my quest for accuracy.”

Boy, does that ever sound familiar. This whole post sounds like it could have come from my experiences with my H’s family. The lunar calendar helps to keep things nice and complicated.

I’m glad I’m not the only one!

Pingback: My Writing Process -- Recreating the Past on a Page | Michelle Robin La